Diversity & Hate: A Look at How Hate Acts Impact Minorities

March 11, 2022

Authors: Louis Audet Gosselin, Khaoula el Khalil, Gabriel Larivière & Hiba Zerrougui,

Introduction

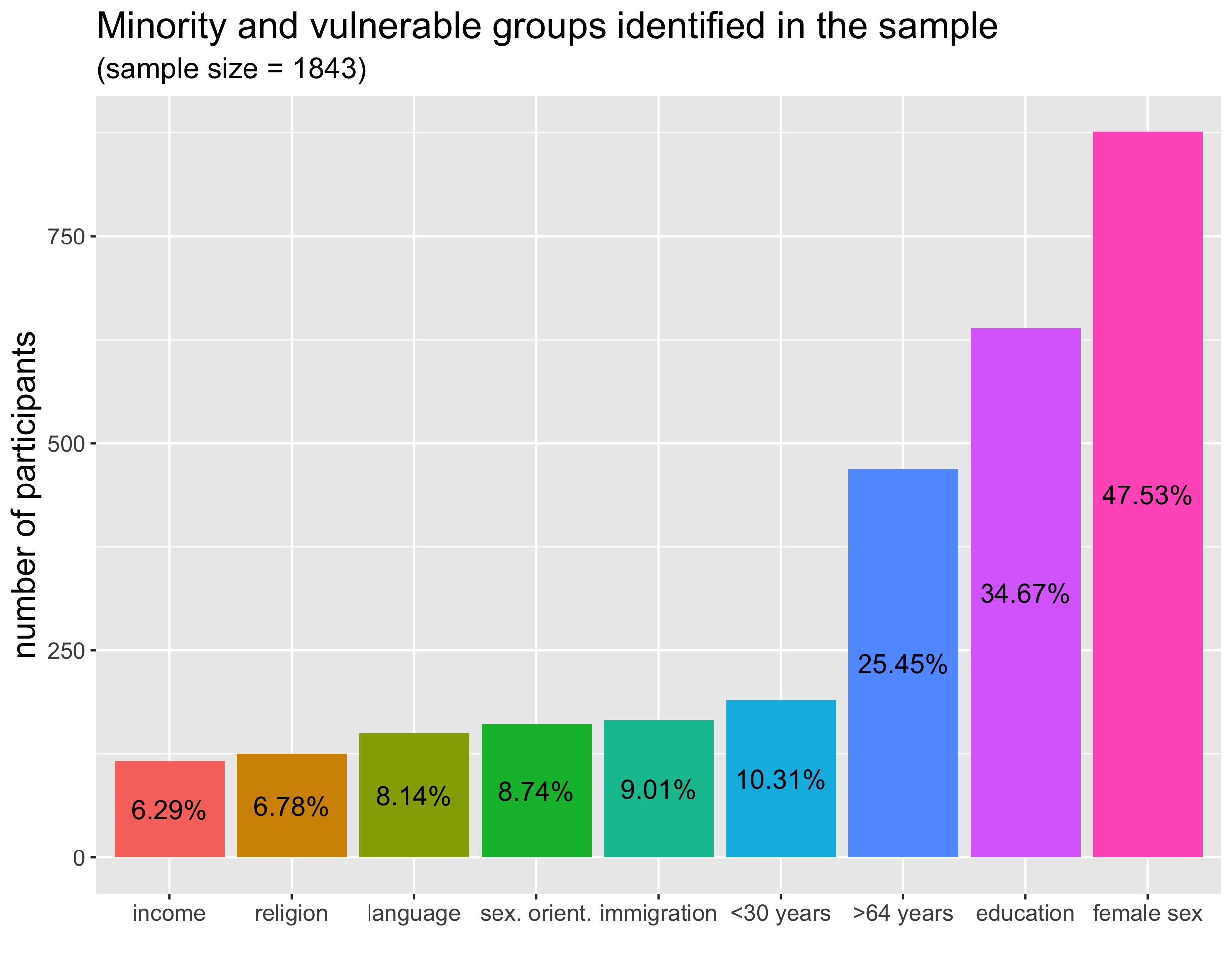

The year 2017 recorded the highest increase in numbers of reported hate crimes in Canada. That year, the Center for the prevention of radicalization leading to violence (CPRLV) mandated the polling firm Vox Pop Labs to conduct a survey to better understand the reality of hate acts in Quebec. A total of 1843 Quebecers responded to the online survey, which asked them information about their socio-economic backgrounds and their experiences of hate acts.

The results from the survey provided the basis of the CPRLV’s recently published report on hate acts in Quebec. In this post, we present some newfindings from our survey regarding the impacts of hate acts on minority groups in Quebec. We show how belonging to minority or vulnerable groups has both aggregated and disaggregated effects for victims of hate acts.

Minority and Vulnerable Groups

The questions asked in our survey allowed for the identification of nine minority groups and vulnerable communities.

Income: participants with an annual income lower than 20,000$

Religion: participants practicing a religion other than Catholicism

Language: participants whose first language is other than French or English

Sexual orientation: participants with a sexual orientation other than heterosexual

Immigration: participants born outside of Canada

<30 years: participants younger than 30 years old

>64 years: participants older than 64 years old

Education: participants who completed a high school education or lower

Female sex: participants with female sexual identity

Intersecting Vulnerable Identities and Experiences of Hate

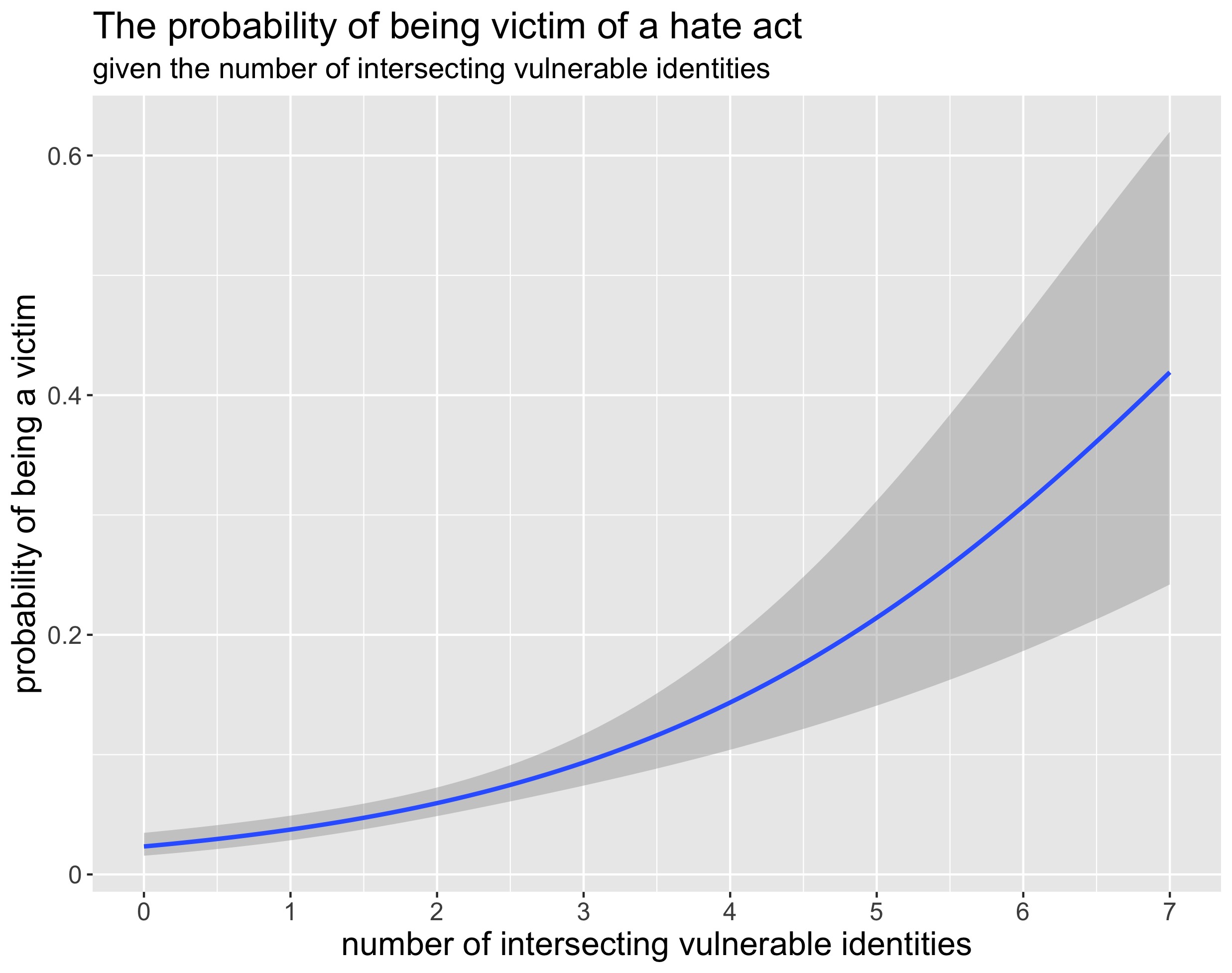

We first assessed whether minority or vulnerable groups are more targeted by hate acts, as previous research suggests. Our survey asked each participant if they had been a victim of a hate crime or a hate incident in the past three years. If the answer was yes for one of those two questions, we counted the participant as a victim of a hate act.

To measure the aggregate effects of demographic variables on victims’ experience of hate, we counted for each participant the number of minority or vulnerable groups to which they belonged. We then built a logistic regression to see whether belonging to several minority groups increased the probability of being a victim of a hate act. The following graph illustrates the result.

The graph shows a strong aggregate effect of intersecting vulnerable identities on the probability of being victim of a hate act, starting at around 0.02 for individuals without any vulnerable identities in our sample, reaching 0.21 for five intersecting vulnerable identities and culminating at 0.42 for seven. However, as the grey areas around the curve illustrate, the margins of error widen as the number of vulnerable identities increases, suggesting that more data is required to precisely estimate the statistical relation.

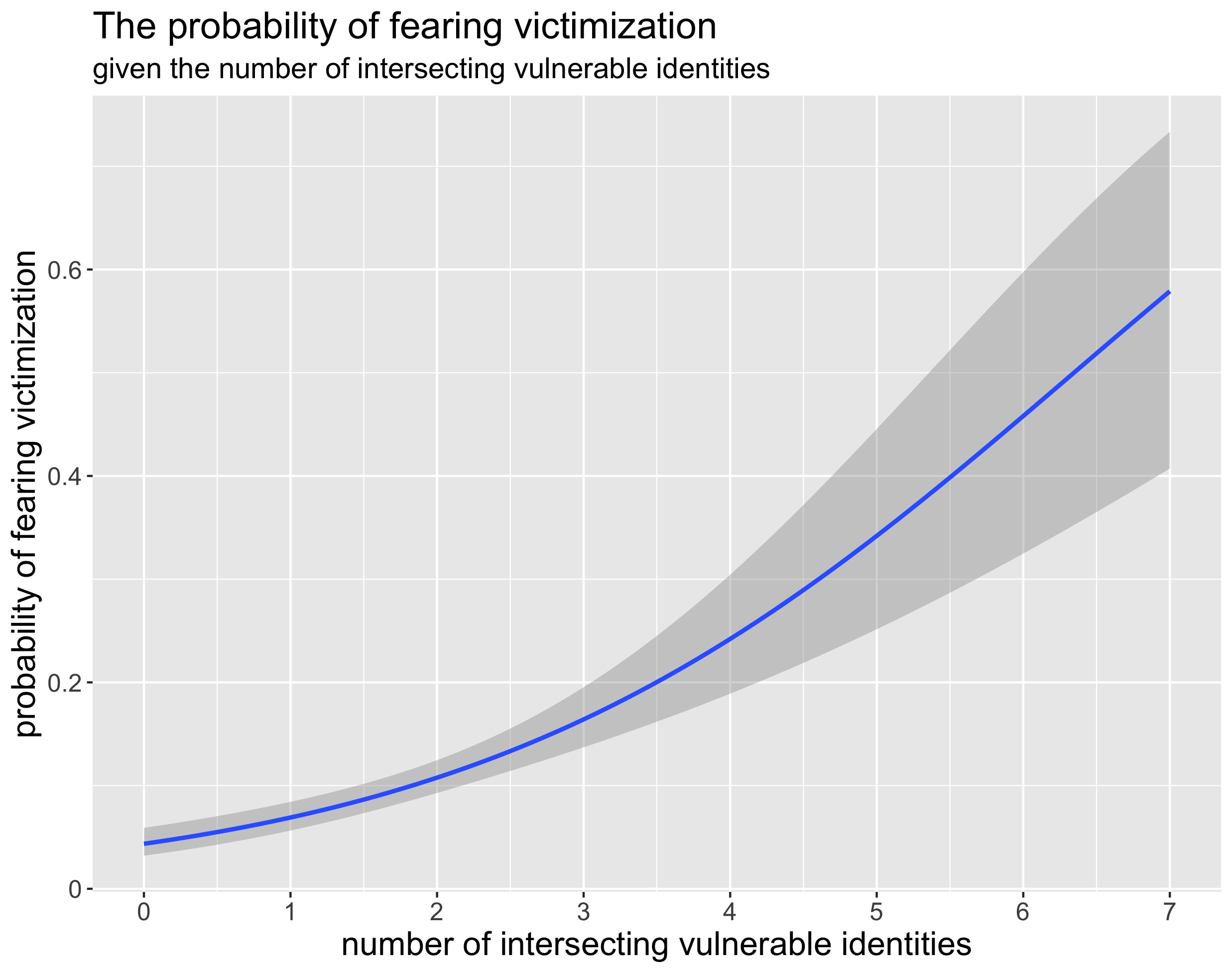

Our survey also gathered information on whether participants feared being a victim of a hate crime or a hate incident in the future. This allowed us to construct another logistic model to see if increasing numbers of intersecting vulnerable identities were linked to a higher probability of fearing hate act victimization, as previous research has also suggested.

The relationship observed in this graph is stronger than in the previous graph measuring the probability of being a victim. That is, being a member of minority or vulnerable groups has even greater aggregated impacts on one’s sense of security. We see here another illustration of a well-known property of hate acts, namely, that they have consequences extending to entire communities, well beyond the immediate victims they target.

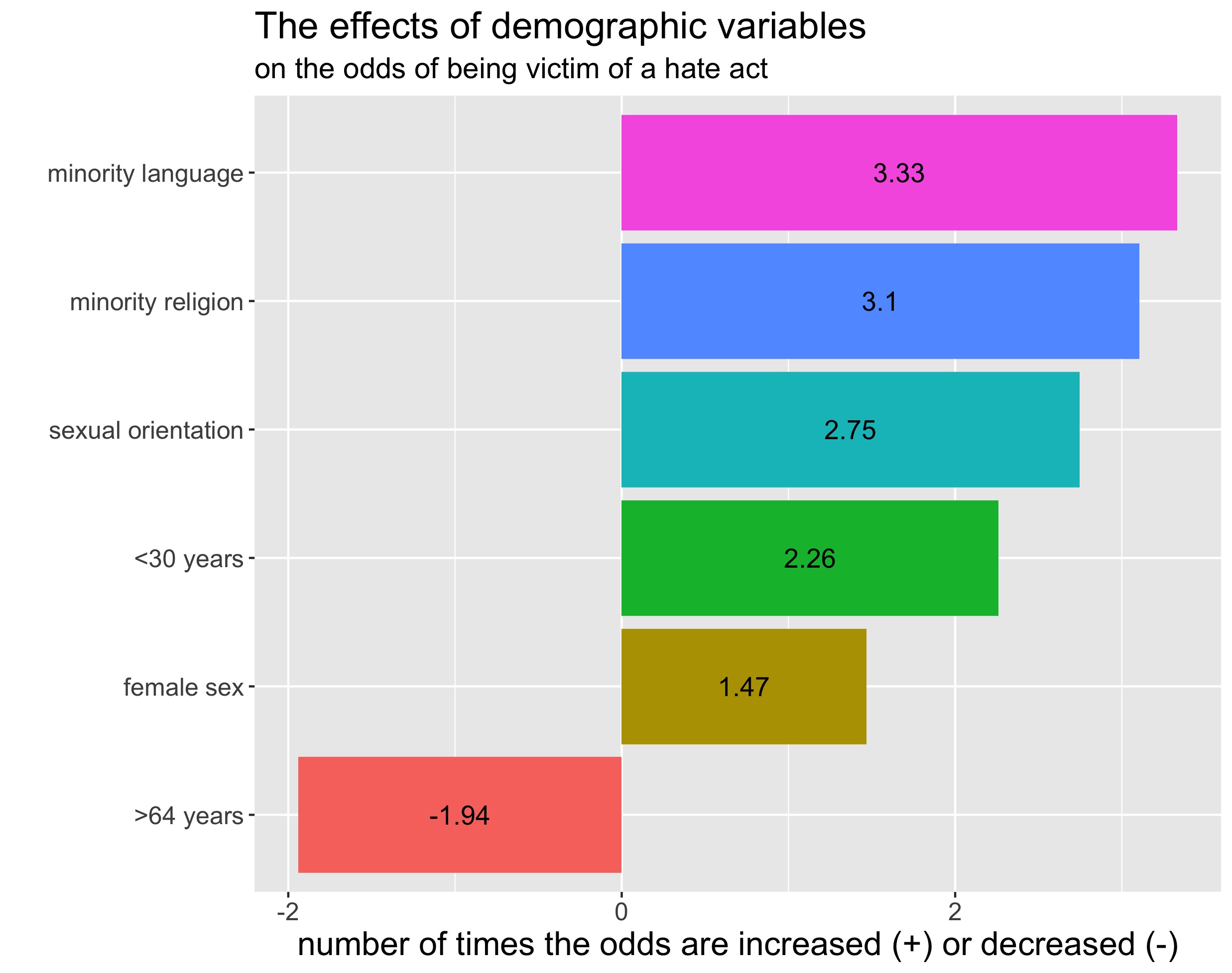

Disaggregated Effects of Vulnerable Identities on Experiences of Hate

While the number of intersecting vulnerable identities is a useful indicator of aggregated effects on minority or vulnerable groups, it provides little information on how much specific vulnerable identities relate to experiences of hate acts. To better understand this reality, we built a logistic regression assessing the effects of the nine vulnerable groups identified on the probability of being a victim of a hate act. The following graph illustrates the multiplicative effect on the odds of being a victim for the demographic variables for which a statistically significant relationship was observed.

As we can see, being a member of a linguistic minority had the strongest effect on the odds of being a victim of a hate act. While similar positive relations were observed for practicing a minority religion, having a sexual orientation other than heterosexual, being younger than 30 years old and being female, we were surprised to see that being older than 64 years old decreased the odds of being victim of a hate crime. It is possible that the survey’s design precluded more vulnerable elderly Quebecers from taking part in the survey.

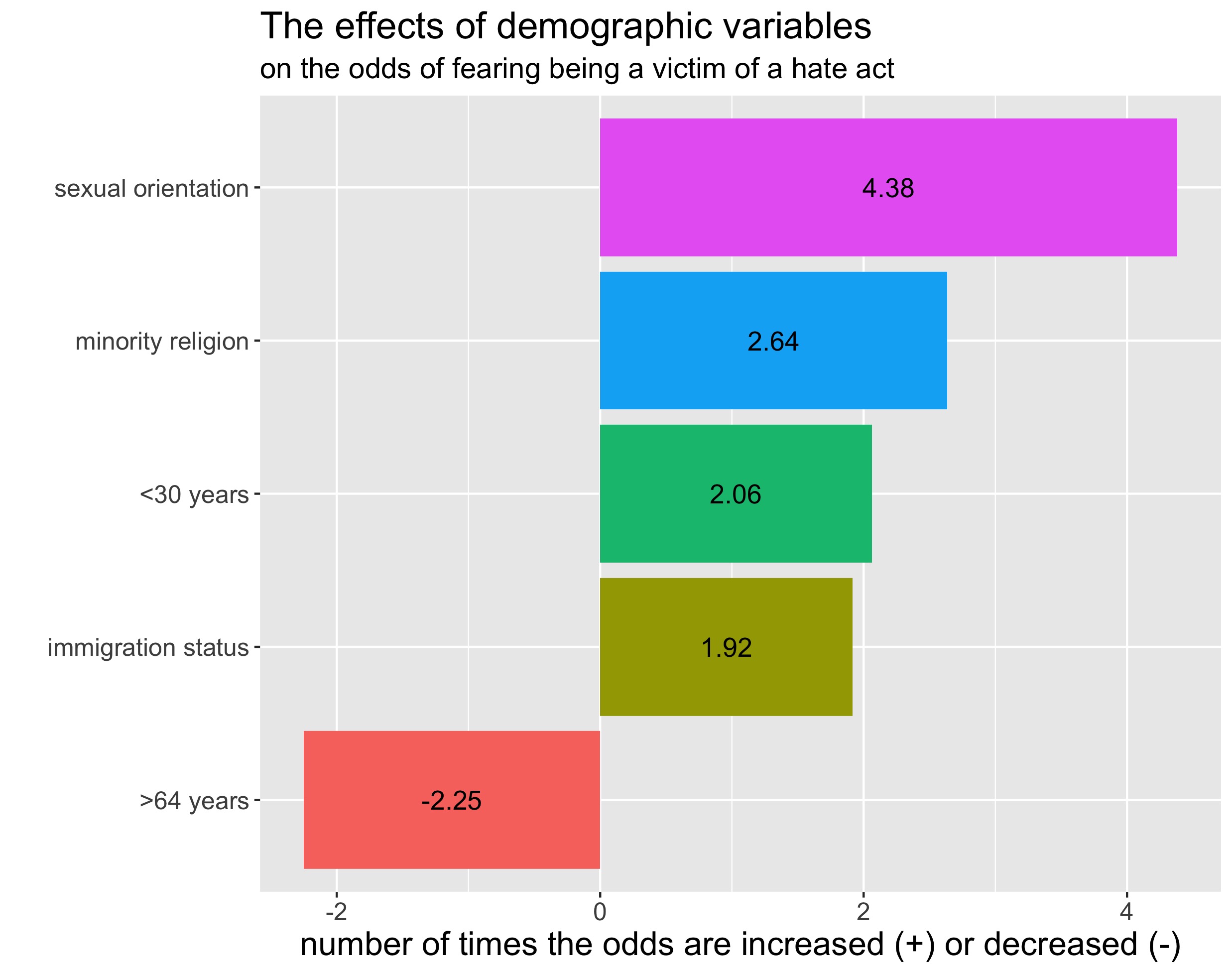

Similarly, we also tested the effects of specific demographic variables on the probability of fearing being a victim of a hate act.

The differences between the two graphs suggest that victimization and fear of victimization are linked to demographic variables in similar but distinct ways. Notably, having a first language other than French or English significantly increases the odds of victimization, but it is not linked to the fear of victimization in a meaningful way. Moreover, being female increases the odds of being a victim but not of fearing victimization; reversely, being born outside of Canada increases the odds of fearing victimization but not of being a victim.

Given the small size of our sample, none of these conclusions can be taken as definitive. Instead, they are invitations to further study the complicated interactions between minority and vulnerable identities and the many experiences of hate acts.

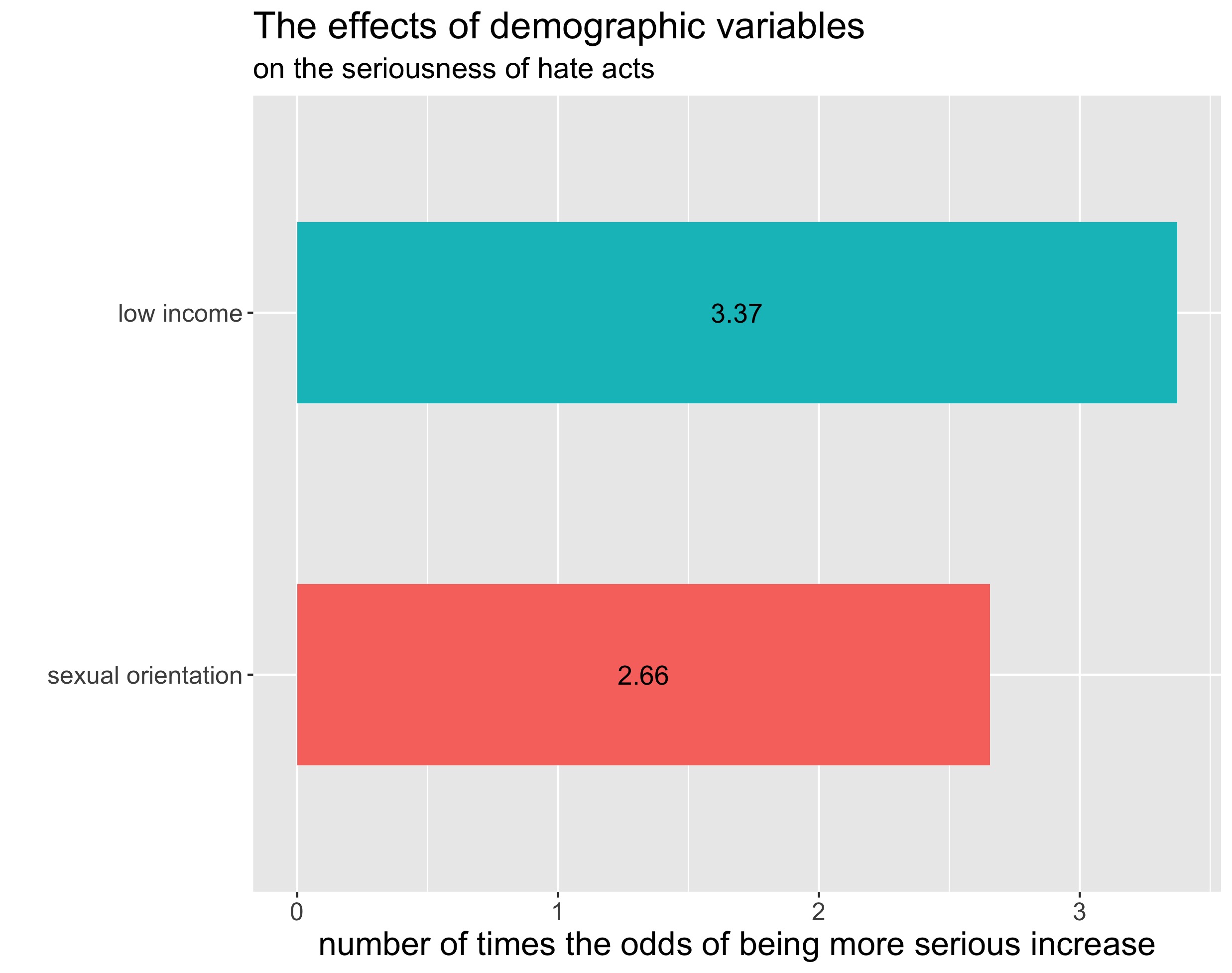

Finally, victims of hate acts were asked in our survey to assess how serious the hate acts they had experienced were, with answers ranging between “Benign” - “Not very serious” - “Serious” - “Very serious”. Using a proportional logistic ordinal regression, we were able to test if certain vulnerable identities increased the likelihood that hate acts would be more serious. Only two demographic variables made hate acts more serious in a statistically significant way, as represented in the following graph.

Our results suggest that having a lower annual income multiplies the odds by 3.37 for a victim that they will be subject to a more serious hate act. For example, if a middle-class individual is victim of a “Serious” hate crime, the odds that the same hate crime would be “Very serious” are multiplied by 3.37 whenever the victim is from a lower socio-economic background. Additionally, whenever a victim also has a sexual orientation other than heterosexual, the odds that the same hate crime would be “Very serious” are multiplied by a total of 8.96 (3.37 × 2.66).

Conclusion

The present blog post highlighted some significant dynamics pertaining to the relationship between hate acts and minority and vulnerable groups. More details about the reality of hate acts in Quebec in our recently published report on the subject matter.

The results from our survey presented here show that membership in minority or vulnerable groups has both aggregated and disaggregated effects. In particular, the more intersecting vulnerable identities an individual has, the more likely they are to be victim of a hate act, and the more likely they are to fear being a victim in the future. On the other hand, our study suggests that such aggregated effects are driven by different vulnerable identities, as different minority group memberships have different effects on the probability of being a victim and on the probability of fearing future victimization.

Research team of the Center for the Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence

Louis Audet Gosselin, PhD

Scientific and Strategic Director

Khaoula el Khalil, MA

Research Advisor

Gabriel Larivière, MA

Research Advisor

Hiba Zerrougui, PhD candidate

Research Advisor

The CPRLV prevents radicalization leading to violence and hate-motivated behaviours by educating, mobilizing and supporting the people of Montreal and Quebec in a community-based approach that is deployed in order to take pre-emptive action, oriented towards accessibility for all, in collaboration with partners from all backgrounds and rooted in both scientific and practical expertise.