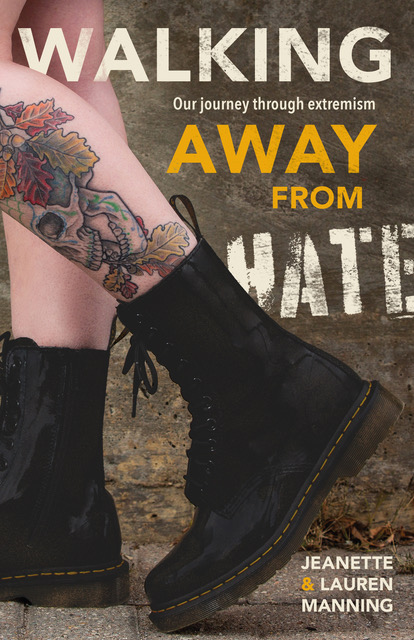

Walking Away From Hate: Reflections

September 8, 2021

Walking Away From Hate: Reflections

Jeanette & Lauren Manning

Like all great ideas—ha-ha—our memoir, “Walking Away from Hate” (Tidewater Press, 2021) came about while my mom was nagging me to tidy my room.

Like all great ideas—ha-ha—our memoir, “Walking Away from Hate” (Tidewater Press, 2021) came about while my mom was nagging me to tidy my room.Actually, she was standing beside a heap of my clean clothes, having just finished reading “Small Great Things” by Jodi Picoult when asked me about the author’s source, Frankie Meeink, who’d written his own memoir, “Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead—The Frankie Meeink Story.”

“Want to read it?” I asked, handing it to her. She seemed to have forgotten she’d bought it for me for Christmas.

A week later she came back. “These people Frankie talks about…are they the same ones you’re friends with?”

“Yup,” I laughed. “They’re with Life After Hate now but they were in the movement too.”

When she asked me if my experiences were similar to theirs, I simply said yes. We’d never talked about my involvement in the far-right and I wasn’t sure how she’d feel hearing about it but slowly, she started questioning me and just as slowly, I began to open up.

“I wish I had known all of this back then,” she said eventually. “I might have done things differently. Too bad kids don’t come with manuals.”

My mom had, on countless occasions, said she wished she’d had a book or resource to refer to while I was submerged in violent extremism. Back in 2007, there was very little online so she navigated my anger, new-found beliefs and distain for our middle-class way of life, with only her mother and my brother for support. We both realized there had to be other parents looking for guidance and that was when she said, “I need to write a book—the book I never had.”

But to do that she needed my story too. For the longest time, my mom had chalked up most of my problems to grief at my dad’s passing when I was 16 years of age. As we began discussing my far-right involvement—joining my first crew at eighteen, living in the dirty basement of an internet café, couch-surfing, switching crews only to be beaten by my so-called friends, finding myself living in not one but two shelters, finding brotherhood with the Hammerskins, becoming friends with two guys who were like older brothers, finding stability in my first long-term relationship and eventually, realizing the movement would never give me what I really wanted—my mom realized my dad’s death was only part of what had lead me to search for outside validation.

The experience of writing “Walking Away” together was cathartic; we had no choice but to ask each other difficult questions and in turn, to give and receive painfully honest answers. “Pretend I’m your editor,” my mom said to me one night. “Not your mother. Don’t worry if what you say will hurt me. It’s more important to get it all out.” And while many of those answers were not what we expected nor wanted to hear, to lie or skirt the truth would have been unfair to those who would eventually read our story.

Once we finished the first draft, my mom’s friend edited it for us. She raised more challenging questions and there were days when I’d throw up my hands and yell, “What the f**k does she want to know that for?” but we kept going. The more we wrote, the more surprised we were by the parallels we saw between our lives; both of us had been looking for a sense of belonging, someone who would understand us, and both of us wore scars from my grandfather’s narcissism.

Extremism is very much like addiction; not only is the addict impacted but their family is as well. In the months since “Walking Away” was published, my mother, preparing various presentations and resource booklets, has realized just how little she knew when I was knee-deep hate. I too, see my involvement much clearer in hindsight.

On the surface, “Walking Away from Hate” is the story of my descent and involvement into white supremacy and what lead me there. It’s the story of my disengagement and what I’ve learned about myself since but beneath it all, this is really the story of family, the impact we each have on one another and the legacy of generational trauma.

And more importantly, our story is proof that together, families can break the cycle of hate.